Since 1935, Florence has been home to a goldsmith’s workshop specializing in silverwork that has gradually established itself as a true academy of the craft. The founder Carlo Foglia first, then his son Giuliano, and for many years now his grandson Lorenzo have all helped write the recent history of the silversmith’s art, creating extraordinary objects and training chasers who have taken their expertise not only throughout the city but around the world.

Today, the works of Lorenzo Foglia—named a MAM, Maestro d’Arte e Mestiere, in 2018—are the mature fruit of an absolute command of traditional techniques, a broad historical culture, and an expressive freedom which—much like in the finest Renaissance workshops—elevate his sculptures and all his silverwork to the status of high art. In his words, one senses all the awareness and passion of a craftsperson who looks to Cellini and Leonardo as guiding spirits.

Maestro, can you tell us how your story began?

It all began with my grandfather Carlo, born in 1910. He was not Tuscan but Lombard, from Erba. After graduating from the Brera Academy of Fine Arts in Milan, he decided to move and open his first goldsmith’s workshop in Florence, which he considered—even more than Paris—the heart of the tradition of this craft. My father Giuliano joined him, and then I arrived: at just fourteen I decided to leave school and enter the workshop to draw, chase, and hammer metal. To me, it was the most beautiful game in the world! If I later went back to studying—first in high school and then at university—it was to look at the craft from a more detached perspective and to understand, first and foremost, myself.

Did such an early and hands-on training become a limitation or an advantage?

Although entirely familial—one might say made in Foglia—my training was not lacking in theoretical depth; on the contrary, it was like an academy. My grandfather, whom I knew for only a few years, and my father passed on to me the enormous importance of the foundations that must accompany practice, and in those years a great many Florentine chasers trained in our workshop. I have never approached a sculpture without first studying its theoretical development and proportions. But I had the immense advantage of fully experiencing the workshop: an irreplaceable school in the dimension of reality, one that not only allows for constant dialogue but also lets you “steal,” with your eyes, the secrets of the craft.

Stylistically, what has the Foglia workshop contributed to the silversmith’s art?

My grandfather introduced to Florence a Baroque-leaning style, made of powerful repoussé work that was foreign to the Florentine tradition—typically more precise and delicate but also more cerebral, at least in silverwork. The forcefulness of the Baroque was, instead, part of the Lombard heritage.

I have always tried to learn as much as possible and to acquire the highest level of technical mastery, knowing that training does not create artists but skilled artisans, just as a conservatory does not necessarily produce great musicians but good music teachers. Technique is a starting point; mastering it is a doorway to expressing oneself freely.

And in which direction has your creativity evolved?

In the early 2000s, the silvermaking sector was in crisis. Wealthy families—the natural clientele for objects crafted in precious metals—were no longer interested in reproductions of Baroque service sets, which they already had at home for generations. Mass production began, which trivialized silver and was also environmentally unsustainable. Buying a silver object should be like going to a good delicatessen, choosing the finest product, and having it sliced to order. There should be no single-serve portions packaged in plastic! It is a luxury, and as such it is born of desire, not necessity.

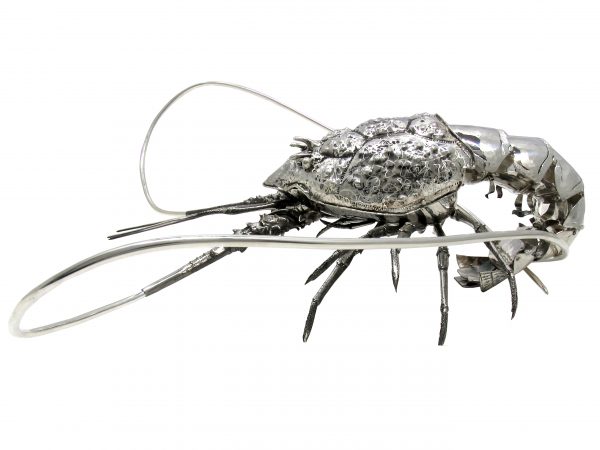

I decided to take a leap into the void, starting to design in a completely free manner, unbound by stylistic or technical limits. I avoided letting my experience constrain my creativity—pushing me to choose certain solutions only because they were the ones codified by the perspective of know-how. I freed myself from function, devoting myself to sculpture, seeking to create objects people could fall in love with, and only afterward worrying about how to make them.

What is your vision of the relationship between artisan and artist?

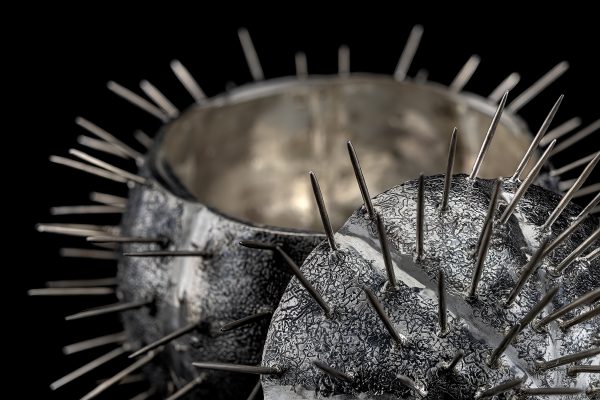

The artisan works within the bounds of their training; the craft is the more academic component. To evolve, one must violate certain stylistic norms, introducing an element of novelty. It is the artistic component that takes on these violations—or variations—which may later become codified themselves and thus fall back within the realm of craftsmanship. It is the passage from minor to major art, the one accomplished by geniuses such as Benvenuto Cellini in sculpture or Leonardo in painting. The Renaissance was born precisely in the Florentine goldsmiths’ workshops, where wealthy patrons entrusted trusted artists with the precious materials needed to create something new and extraordinary.

You collaborate with designers and major companies. Do you enjoy cross-pollination?

Yes, it is essential to break canonical, academic balances. Some companies come to me to disrupt the overly mechanical representation of one of their objects, to invent a detail that interrupts seriality—a pseudo-perfection that is not truly perfect. The market tires of automatism; it wants the irregularity that creates perfection. Humanity is not a matter of being or not being, zero or one, as in binary code—it is everything in between. A machine would produce identical statues, whereas identity is born from the sum of imperfections.

For years now you have also been teaching. Do you enjoy passing on your know-how to younger generations?

One is not a Master unless there are pupils. It is a shared growth, because when you teach you discover reality through the eyes of the learner, who is like a child discovering the world. It is a responsibility, because what you teach will become, for the student, something like an axiom. You must seek answers within yourself and convey them with due delicacy. Having trained many foreigners who come to Florence, I have “children of the craft” all over the world, and it is moving to find in their work the traces of what I have taught them.