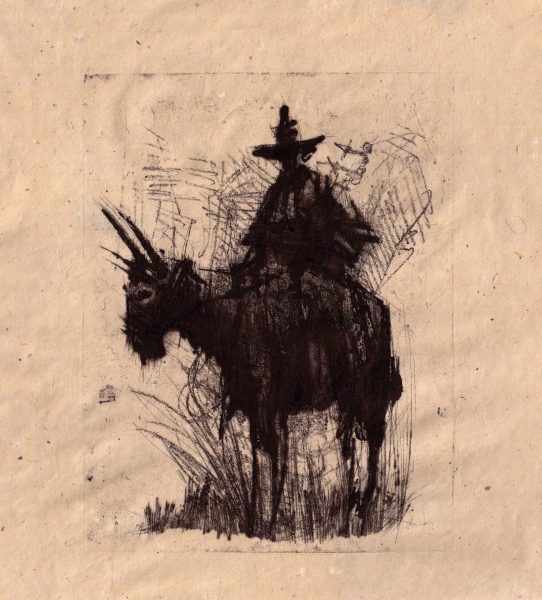

Hands that care are not only those of medical professionals or body practitioners. More broadly, they are the hands of artisans — hands that tend to the material of the world, mastering the very technique of beauty. With this belief, Patrizia Ramacci, master craftswoman in plasterwork and founder of the Bottega d’Arte Gypsea in Gubbio, has created a poetic and ambitious project, constantly evolving: the Archive of Masterful Hands, a collection of plaster casts of the hands of outstanding Italian artisans from every field. A tribute intended to grant them a form of immortality, but also a celebration of the intimate joy of making that those hands embody.

Patrizia, to begin with, can you tell us how you became an artisan?

I did not come from an artisan family; my background is in art and restoration. When my husband Vittorio and I decided to open our workshop, Gypsea, in the historic centre of Gubbio, we imagined reviving a craft that had disappeared from our area—plasterwork—where ceramics and wrought iron had always prevailed. We became an Art Workshop, even though it took me years to acknowledge it, even to myself. Seeking new paths has always been a constant in our lives. We dedicated ourselves both to restoration and to contemporary creation, offering original solutions: ceilings faithfully reproducing traditional structures—beams, joists and terracotta tiles—yet made entirely in plaster; or blown-glass spheres adorned with stucco decorations. We dared unusual combinations, mixing brass, wood, fabrics, in a continuous, fertile cross-pollination.

How did the Archive of Masterful Hands come into being?

When my husband suddenly passed away, I had to manage everything on my own, giving up part of the work that belonged to his repertoire. Even though we had always worked side by side, I was not able to carry out some of those processes myself. I found myself asking what I wanted to do next, knowing for certain that I still wanted to work with my hands. And so I questioned precisely this: what happens to the hands of artisans?

And that is when you decided to create a project entirely dedicated to them?

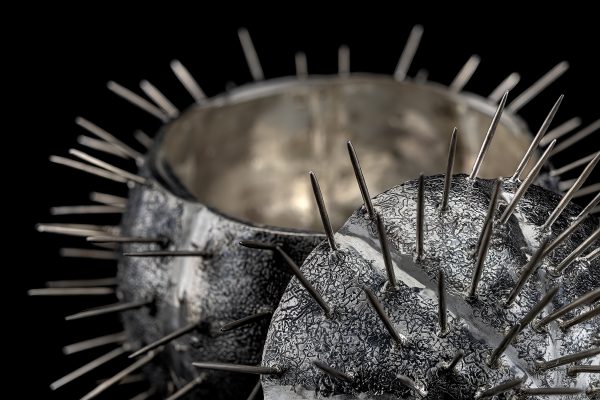

Exactly. The first hands I chose to render immortal, by taking their cast, were those of the last traditional thrower in Gubbio. Then came those of his son, who had returned to the workshop, allowing the tradition to continue. I then travelled to Florence to “capture” the hands of the artisans participating in Artigianato e Palazzo. I did not simply fix the hands in plaster; I fixed the multitude of stories I heard, and the essential connections those hands expressed. This is why all my casts are “mortised”: the internal connecting structures are visible all around, metaphorically displaying their bond with the world. They are casts that may seem imperfect, yet by representing the here and now with absolute fidelity, they stand as credible, tangible, and unique witnesses of skilled making.

How was the project received?

After a small initial exhibition in Gubbio, displaying just sixteen hands, came the major showcase at Palazzo dei Consoli in 2024, visited by nearly twenty thousand people, with more than 100 casts on display. It was a great success—partly because we allowed visitors to touch every hand in the exhibition, an unusual approach in the art world, and partly because they could listen to the voices of the artisans themselves, recounting their own time of making.

Who is included in the archive today?

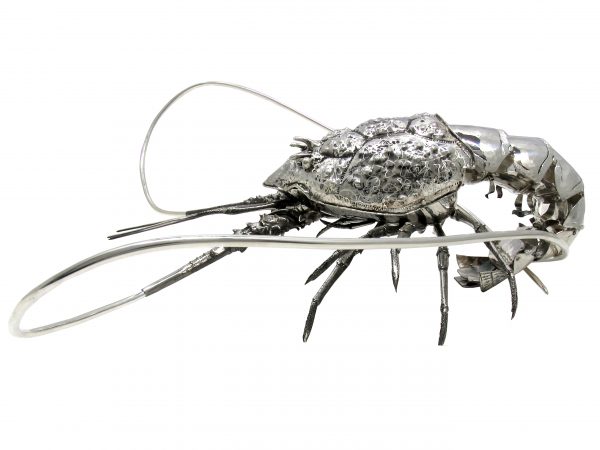

Our archive is a collection of encounters, stories and testimonies. We have sought hands for many reasons—sometimes focusing on individual talent, other times on broader aspects such as the longevity of certain trades and workshops. Recently, I went to Venice to take the casts of artisans from legendary ateliers such as Barovier & Toso, Orsoni, and Bevilacqua. We have also welcomed artists who, as soon as I described the project, immediately wished to be part of it—Michelangelo Pistoletto and Ugo La Pietra among them. The archive today holds more than 200 hands, and it continues to grow and evolve.

What, for you, is the project’s deepest meaning?

In my view, there are two distinct yet equally vital dimensions. One concerns immortality: the desire to leave a personal imprint destined to endure. It reflects the deeply human need—for artisans as for everyone—of attention and recognition. The second is an anthropological dimension linked to the intimate pleasure and sheer happiness of making, an aspect still little known and seldom explored, regardless of the economic framework of the craft.

What is the relationship between an artisan’s skill—symbolised by the hands—and beauty?

For me, beauty is comfort: being in a place and feeling well within it. I think of walking through Venice: you are surrounded by beauty, yet to truly make it your own, you must first understand it. Artisans know the technique of beauty profoundly—its body, its essence, its materiality. Beauty lies in people, in making, in community; it is the care invested in every detail. In short, beauty is feeling—and care.

The Association of the Archive of Masterful Hands has now been established. What are your goals?

The next step is to protect the entire archive and to identify a proper exhibition venue, as all the casts currently reside in my workshop. Displaying them permanently—in a living, active way—would allow us to kindle in visitors that desire to make, which hands naturally evoke. And today, reclaiming our humanity is more necessary than ever, to distinguish ourselves from what is no longer human.

In terms of growth, our numerical goal is highly ambitious, and reaching it will require the support of both public and private institutions, including the Fondazione Cologni dei Mestieri d’Arte: we want to reach one thousand hands!

Bottega d’Arte Gypsea di Patrizia Ramacci

Largo del Bargello, 1 – Gubbio (PG)

Tel. 075 9271016 – Cell.: +39 338 2832388

patrizia@gypsea.com – www.gypsea.com